In preparation for the 2012 Summer Olympics, major new facilities and buildings and are being constructed throughout London, preparing for the onslaught of tens of thousands of spectators and dozens of high profile athletic events. One such project which has been garnering strong reaction from architecture observers and critics is the London Aquatics Centre which will host Olympic swimming, diving, and synchronized swimming events with a seating capacity of 17,500.

The complex sits in the expansive Olympic Park development on the banks of the River Lea canal, a major source of inspiration for the designers. The three-pool complex was designed by the award-winning and somewhat controversial architect Zaha Hadid through her firm Zaha Hadid Architects who describe their process as “inspired by the fluid geometry of water in motion.”

Zaha Hadid has been recognized internationally for her academic work and aptitude for emerging technologies in architecture and design. The Iraqi-British architect won the Pritzker Prize in 2004 and was included by Time Magazine as one of their top 100 Most Influential People in the World list in 2010.

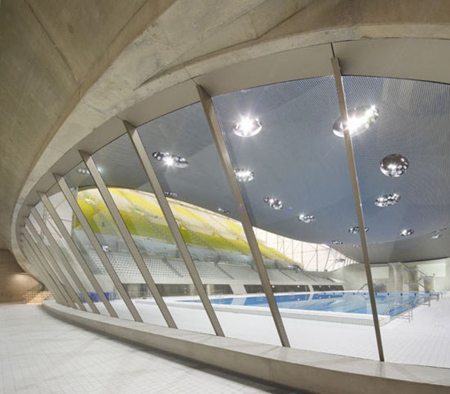

A massive engineering feat, the 3,000 ton roof structure was lifted and placed onto supports in a single motion and rests at three points.

As with everything Zaha designs – strong reactions are common. Architecture critic Rowan Moore explains to the Observer his disappointment with the “blown-up, go-faster” temporary structures that he feels obscure the form of the main building. The temporary structures are intended to seat an additional 15,000 visitors for the Olympics before being dismantled and used again for the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janiero. The result of the temporary structures is two wedge-shaped protrusions from the main structure’s rounded shape where glass walls will eventually take place.

Moore does go on, however, to credit the architects on the scale and form of the interior which he describes as “like a body more than something constructed out of pieces.”

The concrete diving platforms of the center are built into the structure as complimentary to the greater structure, and work as architectural punctuations of the space.

The wave of the roof sweeps up from the ground and inside results in a ceiling that sinks in the center to subtly separate the diving and swimming event areas.

The ceiling above the pools is thatched with concrete beams and lighting pockets that recall the Brutalism and Post-Modernism of the Nixon Era with a simple and decidedly contemporary twist.

The development of London’s Olympic Park has been touted by politicians and planners as an engine for revitalization of the Stratford area of East London. The Boston Globe reports that roughly $10 billion of the Olympic budget was allotted to development in one of the most disadvantaged areas of Britain. Connected by massive pedestrian bridge, the Aquatics Centre will be accessible from the under-construction Stratford International high speed rail station and other transit services through the huge Westfield Stratford City shopping center currently undergoing a massive renovation and expansion. As such, there is huge pressure on planners and architects to design space that will work not just for the duration of the Olympics, but that will continue to be relevant and integrated with the local community well into the future.

After the games, the temporary seating structures will be removed and the new park space will be christened the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park to mark the monarch’s Diamond Jubilee. Further greening of the area will continue as planners adapt the massive space to its role as a neighborhood and regional center.